Bird Identification – Flicker – High-hole – Clape – Golden-winged – Woodpecker – Yellow-hammer – Yucker

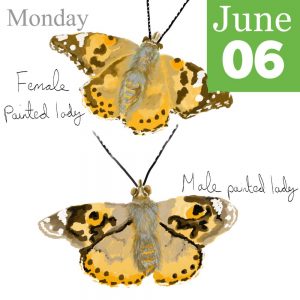

Why should the flicker discard family traditions and wear clothes so different from those of his relations? His upper parts are dusty brown, narrowly barred with black, and the large white patch on his lower back, so conspicuous as he flies from you, is one of the best marks of identification on his big handsome body. His head is gray with a black streak below the eye, and a scarlet band across the nape of the neck, while the upper side of the wing feathers is black relieved by golden shafts. Underneath, the wings are a lovely golden yellow, seen only when the bird flies toward you. His breast, which is a pale, pinkish brown, is divided from the throat by a black crescent, smaller than the meadowlark’s, and below this half-moon of jet there are many black spots. He is quite a little larger than a robin, the largest and the commonest of our five non-union carpenters.

See him feeding on the ground instead of on the striped and mottled tree trunks, where his black and white striped relatives are usually found, and you will realise that he wears brown clothes, finely barred, because they harmonise so perfectly with the brown earth. What does he find on the ground that keeps him there so much of the time? Look at the spot he has just flown from and you will doubtless find ants. These are chiefly his diet. Three thousand of them, for a single meal, he has been known to lick out of a hill with his long, round, extensile, sticky tongue. Evidently this lusty fellow needs no tonic. His tail, which is less rounded than his cousins’, proves that he has little need to prop himself against tree trunks to pick out a dinner; and his curved bill, which is more of a pickaxe than a hammer, drill, or chisel, is little used as a carpenter’s tool except when a nest is to be dug out of soft, decayed wood. Although he can beat a rolling tattoo in the spring, he has a variety of call notes for use the year through. Did you ever see the funny fellow spread his tail and dance when he goes courting? Flickers condescend to use old holes deserted by their relatives who possess better tools. You must have noticed all through these bird biographies that the structure and colouring of every bird are adapted to its kind of life, each member of the same family varying according to its habits. The kind of food a bird eats and its method of getting it, of course, bring about most, if not all, of the variations from the family type. Each is fitted for its own life, “even as you and I.”

Like your pet pigeon, the hummingbird, and several other birds, parent flickers pump partly digested food from their own stomachs into those of their hungry babies. Imagine how many trips would have to be taken to a nest if ants were carried there one by one! How can the birds be sure they will not thrust their bills through the eyes of their blind, naked and helpless babies in so dark a hole? It must be very difficult to find the mouths and be sure none is neglected. Like the little pig you all know about, I suspect there is always at least one little flicker in the dark tree-hollow that “gets none” each trip.