Bird Identification – Belted Kingfisher – The Halcyon

This Izaak Walton of birddom, whom you may see perched as erect as a fish hawk on a snag in the lake, creek or river, or on a dead limb projecting over the water, on the lookout for minnows, chub, red fins, samlets or any other small fry that swims past, is as expert as any fisherman you are ever likely to know. Sharp eyes are necessary to see a little fish where sunbeams dance on the ripples and the refracted light plays queer tricks with one’s vision. Once a victim is sighted, how swiftly the lone fisherman dives through the air and water after it, and how accurately he strikes its death-blow behind the gills! If the fish be large and lusty it may be necessary to carry it to the snag and give it a few sharp knocks with his long powerful bill to end its struggles. These are soon over, but the kingfisher’s have only begun. See him gag and writhe as he swallows his dinner, head first, and then, regretting his haste, brings it up again to try a wider avenue down his throat! Somebody shot a kingfisher which had tried to swallow so large a fish that the tail was sticking out of his mouth, while its head was safely stored below in the bird’s stomach. After the meat digests, the indigestible skin, bones, and scales of the fish are thrown up without the least nausea.

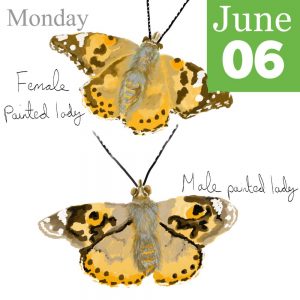

A certain part of a favourite lake or stream this fisherman patrols with a sense of ownership and rarely leaves it. Alone, but self-satisfied, he clatters up and down his beat as a policeman, going his rounds, might sound his rattle from time to time. The rattle-headed bird knows every pool where minnows play, every projection along the bank where a fish might hide, and is ever on the alert, not only to catch a dinner, but to escape from the sight of the child who intrudes on his domain and wants to “know” him. You cannot mistake this big, chunky bird, fully a foot long, with grayish-blue upper parts, the long, strong wings and short, square tail dotted in broken bars of white, and with a heavy, bluish band across his white breast. His mate and children wear rusty bands instead of blue. The crested feathers on top of his big, powerful head reach backward to the nape like an Indian chief’s feather bonnet, and give him distinction. Under his thick, oily plumage, as waterproof as a duck’s, he wears a suit of down under-clothing.

No doubt you have heard that all birds are descended from reptile ancestors; that feathers are but modified scales, and that a bird’s song is but the glorified hiss of the serpent. Then the kingfisher and the bank swallow retain at least one ancient custom of their ancestors, for they still place their eggs in the ground. The lone fisherman chooses a mate early in the spring and, with her help, he tunnels a hole in a bank next a good fishing ground. A minnow pool furnishes the most-approved baby food. Perhaps the mates will work two or three weeks before they have tunnelled far enough to suit them and made a spacious nursery at the end of the long hall. Usually from five to eight white eggs are laid about six feet from the entrance on a bundle of grass, or perhaps on a heap of ejected fish bones and refuse. While his queen broods, the devoted kingfisher brings her the best of his catch. At first their babies are as bare and skinny as their cuckoo relatives. When the father or mother bird flies up stream with a fish for them, giving a rattling call instead of ringing a dinner bell, all the hungry youngsters rush forward to the mouth of the tunnel; but only one can be satisfied each trip. Then all run backward through the inclined tunnel, like reversible steam engines, and keep tightly huddled together until the next exciting rattle is heard. Both parents are always on guard to drive off mink, rats and water snakes that are the terrors of their nursery.

Waiting for mamma and fish.

Waiting for mamma and fish.

Young belted kingfisher on his favourite snag.

Young belted kingfisher on his favourite snag.

Kingfisher on the look-out for a dinner.

Kingfisher on the look-out for a dinner.