Bird Identification – Towhee – Chewink – Ground Robin – Joree

From their hunting-ground in the blackberry tangle and bushes that border a neighbouring wood, a family of chewinks sally forth boldly to my piazza floor to pick up seed from the canary’s cage, hemp, cracked corn, sunflower seed, split pease, and wheat scattered about for their especial benefit. One fellow grew bold enough to peck open a paper bag. It is a daily happening to see at least one of the family close to the door; or even on the window-sill. The song, the English, the chipping, the field, and the white-throated sparrows—any one or all of these cousins—usually hop about with the chewinks most amicably and with no greater ease of manner; but the larger chewink hops more energetically and precisely than any of them, like a mechanical toy.

Heretofore I had thought of this large, vigorous bunting as a rather shy or at least self-sufficient bird with no desire to be neighbourly. His readiness to be friends when sure of the genuineness of the invitation, was a delightful surprise. From late April until late October my softly-whistled towhee has rarely failed to bring a response from some pensioner, either in the woodland thicket or among the rhododendrons next to the piazza where the seeds have been scattered by the wind. Chewink, or towhee comes the brisk call from wherever the busy bunting is foraging. The chickadee, whippoorwill, phoebe and pewee also tell you their names, but this bird announces himself by two names, so you need make no mistake.

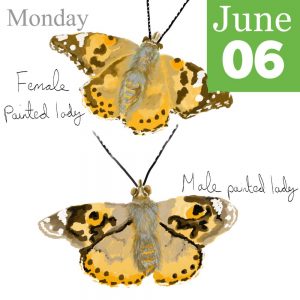

Because he was hatched in a ground nest and loves to scratch about on the ground for insects, making the dead leaves and earth rubbish fly like any barnyard fowl, the towhee it often called the ground robin. He is a little smaller than robin-redbreast. Looked down upon from above he appears to be almost a black bird, for his upper parts, throat and breast are very dark where his mate is brownish; but underneath both are grayish white with patches of rusty red on their sides, the colour resembling a robin’s breast when its red has somewhat faded toward the end of summer. The white feathers on the towhee’s short, rounded wings and on the sides of his tail are conspicuous signals, as he flies jerkily to the nearest cover. You could not expect a bird with such small wings to be a graceful flyer.

Rarely does he leave the ground except to sing his love-song. Then, mounting no higher than a bush or low branch, he entrances his sweetheart, if not the human critic, with a song to which Ernest Thompson Seton supplies the well-fitted words: Chuck-burr, pill-a will-a-will-a.