Bird Identification – Red-shouldered Hawk – Hen Hawk – Chicken Hawk – Winter Hawk

Let any one say “Hawk” to the average farmer and he looks for his gun. For many years it was supposed that every member of the hawk family was a villain and fair game, but the white searchlight of science shows us that most of the tribe are the farmers’ allies, which, with the owls, share the task of keeping in check the mice, moles, gophers, snakes, and the larger insect pests. Nature keeps her vast domain patrolled by these vigilant watchers by day and by night. Guns may well be turned on those blood-thirsty fiends in feathers. Cooper’s hawk, the sharp-shinned hawk, and the goshawk, that not only eat our poultry, but every song bird they can catch: the law of the survival of the fittest might well be enforced with lead in their case. But do let us protect our friends, the more heavily built and slow-flying hawks with the red tails and red shoulders, among other allies in our ceaseless war against farm vermin!

In the court of last appeal to which all our hawks are brought—I mean those scientific men in the Department of Agriculture, Washington, who examine the contents of birds’ stomachs to learn just what food is taken in different parts of the country and at different seasons of the year—the two so-called “hen hawks” were proved to be rare offenders, and great helpers. Two hundred and twenty stomachs of red-shouldered hawks were examined by Dr. Fisher, and only three contained remains of poultry, while one hundred and two contained mice; ninety-two, insects; forty, moles and other small mammals; fifty-nine, frogs and snakes, and so on. The percentage of poultry eaten is so small that it might be reduced to nothing if the farmers would keep their chickens in yards instead of letting them roam to pick up a living in the fields, where the temptation to snatch up one must be overwhelming to a hungry hawk. Fortunately these two beneficent “hen hawks,” are still common, in spite of our ignorant persecution of them for two hundred years or more.

Toward the end of summer, especially in September, when nursery duties have ended for the year and the hawks are care free, you may see them sailing in wide spirals, delighting in the cooler stratum of air high overhead. Balancing on wide, outstretched wings, floating serenely with no apparent effort, they enjoy the slow merry-go-round at a height that would make any child dizzy. Sometimes they rise out of sight. Kee you, kee you, they scream as they sail. Does the teasing blue jay imitate the call for the fun of frightening little birds?

But the red-shouldered hawk is not on pleasure bent much of the time. Perching is its specialty, and on an outstretched limb, or other point of vantage, it sits erect and dignified, its far-seeing eyes alone in motion trying to sight its quarry—a mouse creeping through the meadow, a mole leaving its tunnel, a chipmunk running along a stone wall, a frog leaping into the swamp, a gopher or young rabbit frisking around the edges of the wood—when, spying one, “like a thunderbolt it falls.”

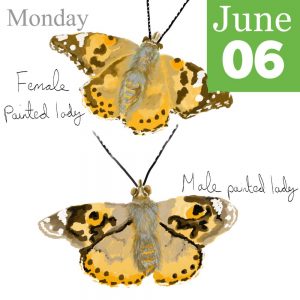

If you could ever creep close enough to a red-shouldered hawk, which is not likely, you would see that it is a powerful bird, about a foot and a half long, dark brown above, the feathers edged with rusty, with bright chestnut patches on the shoulders. The wings and dark tail are barred with white, so are the rusty-buff under parts, and the light throat has dark streaks. Female hawks are larger than the males, just as the squaws in some Indian tribes are larger than the braves. It is said that hawks remain mated for life; so do eagles and owls, for in their family life, at least, the birds of prey are remarkably devoted, gentle and loving.